As most of us might expect, all of the action/reaction/counter-reaction going on surrounding Russia's invasion of the Ukraine has spilled over into things well beyond the borders of both countries. Two stories broke on the impact on the space business.

The first story is that

Russia pulled out of the European Union's launch business

in response to EU sanctions against them. This pushes an April launch

currently being prepared into limbo.

The chief of Russia's main space corporation, Dmitry Rogozin, announced the decision on Twitter Saturday morning, saying his country was responding to sanctions placed on Russia by the European Union. Europe, the United States, and other nations around the world issued significant sanctions on Russia this week after the country's unprovoked invasion of Ukraine.

The affected launch is two Galileo satellites on the "Europeanized" version of a Soyuz rocket for the EU on April 6. There's currently about a dozen Russian technicians and engineers working at the launch site in French Guiana.

This leaves the EU in a bit of a bind.

While the European Commissioner for Space, Thierry Breton, stoically insisted on Saturday that the Galileo or Copernicus constellations wouldn't be affected in terms of continuity or quality of service or even the further development of those systems. The problem is the EU doesn't have a launch vehicle at their disposal for this launch in April - or for either Galileo or Copernicus satellites for the foreseeable future. As Eric Berger at Ars Technica puts it:

Europe's small Vega rockets are not powerful enough to lift the Galileo and Copernicus satellites to their orbits. And the continent's heavy-lift vehicle, Ariane 5, is being retired in favor of the more efficient and cost-effective Ariane 6 rocket. However, all of the remaining Ariane 5 launches are spoken for, and the Ariane 6 rocket probably will not become operational until at least 2023.

So it is not clear what steps Europe might take in the interim, should it need to rapidly launch a Galileo or Copernicus satellite. The only Western company with the spare capacity for such a mission is probably the United States-based SpaceX, but Europe seems unlikely to support a competitor to its institutional launch industry.

Especially a competitor they've derided so often.

The second news story is being widely misquoted, in the rampant, apparently click-driven way everything is, as Dmitry Rogozin (again, chief of Roscosmos, Russia's main space corporation) saying Russia was going to drive the International Space Station out of orbit and into "the US or Europe." Rogozin's Tweets were translated into English and Tweeted by Eric Ralph. My reading of most of the rant is that he's saying almost all of the sanctions are things that are already in place. With regard to ISS de-orbiting, what he said was.

"If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an unguided de-orbit to impact on the territory of the US or Europe?" Rogozin asked. "There's also the chance of impact of the 500-ton construction in India or China. Do you want to threaten them with such a prospect? The ISS doesn't fly over Russia, so all the risk is yours. Are you ready for it?"

Which sounds a lot like he thinks the US is incapable of supplying a rocket

that could correct the slow decay of the ISS' orbit, and thinks his modules

that are docked to the ISS are indispensable. Yes, with no orbital

corrections that decay will cause the ISS to de-orbit, burn up (to some

degree) and then whack somewhere on Earth, but he's not saying he's going to

do it.

In response, NASA said "The new export control measures will continue to allow

US-Russia civil space cooperation. No changes are planned to the

agency’s support for ongoing in-orbit and ground station operations."

They said they intend to continue to cooperate with all their international

partners.

These are just two examples, and I'm sure there are more. As I recall it, the whole reason behind partnering with Russia on the ISS was to give their rocket engineers and scientists something to do besides move to another country and get that new country's ICBM program going. Like most government programs, I bet there isn't a soul on the planet that could tell you if that idea worked.

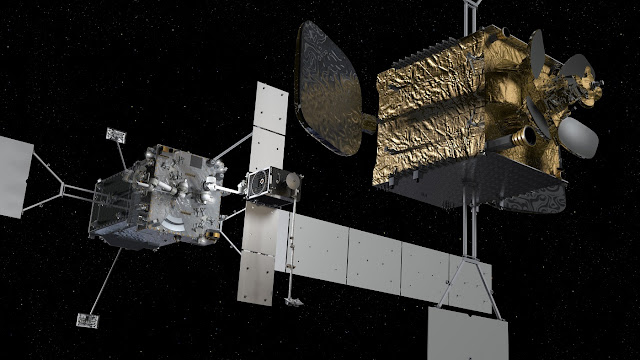

A "Europeanized Soyuz" being prepared for launch at French Guiana in December 2021. European Space Agency photo. Due to the recent timing, I'd guess this could be the booster for the April 6 launch.