The response to a statement like that used to be "funny as in ha-ha, or funny

as in strange?" Funny strange.

Stephen Clark at Ars Technica pointed this out last night, saying "There's a secret reason the Space Force is delaying the next Atlas

V launch." I was quickly going from not having noticed it to the "now

that you've mentioned it" side.

As the title suggests, the weirdness started on the scheduled next launch of

an Atlas V back on April 9th, a mission to carry 27 Kuiper satellites for

Amazon.com's version of a satellite internet constellation like

Starlink. While working on that night's post (about Jared Isaacman's

first senate confirmation hearing), I had the live coverage of that mission

playing audio, so I heard it going on and switched to watch things a couple of

times. It looked like a plain old scrub due to a line of storms

violating some launch criteria or another. No big deal. Happens

fairly often.

I expected (along with many others) that they would do a 24 hour reset and go

the next night. The next morning, a time for the next launch attempt

still hadn't been posted to NextSpaceflight.com. April 9th was Wednesday, and it

wasn't until the weekend that a Monday launch time was announced. Then

that launch date was deleted, too. At some point, I start wondering if

something else really caused the launch scrub and it was just convenient to

blame it on the weather.

At first, there seemed to be a good explanation for the extended turnaround.

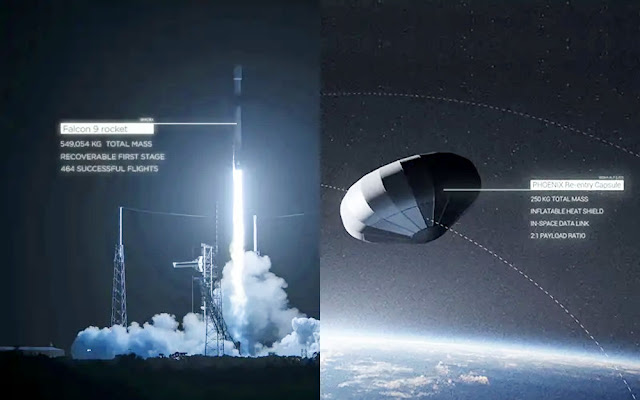

SpaceX was preparing to launch a set of Starlink satellites on a Falcon 9

rocket around the same time as Atlas V's launch window the next day. The

Space Force's Eastern Range manages scheduling for all launches at Cape

Canaveral and typically operates on a first-come, first-served basis.

Except that SpaceX was delayed, too.

It wouldn't have been surprising for SpaceX to get priority on the range

schedule since it had already reserved the launch window with the Space

Force for April 10. SpaceX subsequently delayed this particular Starlink

launch for two days until it finally launched on Saturday evening, April 12.

Another SpaceX Starlink mission launched Monday morning.

There are several puzzling things about what happened last week. When SpaceX

missed its reservation on the range twice in two days, April 10 and 11, why

didn't ULA move back to the front of the line?

Clark says that ULA has always been pretty transparent about launch scrubs,

but they've never said anything detailed about the reasons for waiting to

launch, only saying, "a new launch date will be announced when approved on the

range." After being sure to say, "The rocket and payload are healthy."

Then, a few days ago, SpaceX postponed one of its Starlink missions from Cape

Canaveral without explanation, making this a rather rare week without a launch

on the Eastern Test Range. NextSpaceflight says SpaceX is planning their

next launch early this coming Monday, 4/21 (4:15 AM EDT); that delayed

Starlink mission will launch around 16-1/2 hours later, Monday evening at 8:48

PM EDT. The early morning launch is a Cargo Resupply Mission, Cargo

Dragon, to the ISS and those missions seem to be higher priority to the Space

Force Station.

One more twist in this story is that a few days before the launch attempt,

ULA changed its launch window for the Kuiper mission on April 9 from midday

to the evening hours due to a request from the Eastern Range. Brig. Gen.

Kristin Panzenhagen, the range commander, spoke with reporters in a

roundtable meeting last week. After nearly 20 years of covering launches

from Cape Canaveral, I found a seven-hour time change so close to launch to

be unusual, so I asked Panzenhagen about the reason for it, mostly out of

curiosity. She declined to offer any details.

"The Eastern Range is huge," she said. "It's 15 million square miles. So, as

you can imagine, there are a lot of players that are using that range space,

so there's a lot of de-confliction ... Public safety is our top priority,

and we take that very seriously on both ranges. So, we are constantly

de-conflicting, but I'm not going to get into details of what the actual

conflict was."

Stephen Clark comes to the conclusion that there's something going out in

those 15 million square miles that is making Space Force clamp down on

launches and it's secret enough that they're not going to say anything about

it. There are several possibilities that can be considered, for example,

launches of vehicles that the public isn't supposed to know about.

Perhaps submarine launched missiles or new missiles that the Space Force wants

to keep as secret as possible. That sort of testing, typically leads to

cautions in "Notices to Mariners" for boaters or "Notices to Air Men."

Searches for those kinds of notices don't show any released lately.

It's possible that there's something (or some things) that are broken or that

need some sort of maintenance.

When launches were less routine than today, the range at Cape Canaveral

would close for a couple of weeks per year for upgrades and refurbishment of

critical infrastructure. This is no longer the case. In 2023, Panzenhagen

told Ars that the Space Force changed the policy.

"When the Eastern Range was supporting 15 to 20 launches a year, we had room

to schedule dedicated periods for maintenance of critical infrastructure,"

she said at the time. "During these periods, launches were paused while

teams worked the upgrades. Now that the launch cadence has grown to nearly

twice per week, we’ve adapted to the new way of business to best support our

mission partners."

Perhaps, then, it's something more secret, like a larger-scale, multi-element

military exercise or war game that either requires Eastern Range participation

or is taking place in areas the Space Force needs to clear for safety reasons

for a rocket launch to go forward.

As of this evening, that Atlas V launch (Project Kuiper (KA-01) ) is back on

the schedule. Monday, Apr 28, 7:00 PM EDT

Pushed by trackmobile railcar movers, the Atlas V rocket rolled to the launch pad last week with a full load of 27 satellites for Amazon's Kuiper Internet megaconstellation. Credit: United Launch Alliance