Early this morning before sunrise, SpaceX transported Booster 7 to their orbital

launch facility, at least temporarily being placed where we get a unique view

of the facility. The booster was in place by 7:40AM CDT as the sun was

leaving the frame on the Nerdle Cam. (This screen capture is clearly much later)

That's Booster 4 on the left (with an apparently damaged grid fin or fin rotating mechanism) and B7 in line (visually) with SN20 in the middle of the frame.

The first order of tests is going to be an attempt to torture the booster with the type of loads that it's going to see in use and verify it survives and can work. The emphasis here is a massive mechanical device affectionately known as the ‘can crusher.’ Made up of two large steel structures, that structural test stand’s primary purpose is, to some degree, to attempt to crush Starship test tanks and Super Heavy prototypes. The bottom half of the can crusher was transported to the pad area a week ago Wednesday, March 23.

The Can Crusher bottom on the way to the orbital launch pad area. Photo by BocaChicaGal for NASASpaceflight.com

The major reason for the switch from B4 to B7 is that the Raptor V1.5 engines on B4 have been obsoleted, and the new Raptor V2 engines require a rebuild of the bottom third of the booster. B7 is the first booster designed to use the new engines – and will carry 33 of them, instead of the 29 older Raptors B4 accommodated.

On top of major design simplifications that should slash the cost of manufacturing, Raptor V2’s maximum thrust was boosted from about 185 tons to 230+ tons (~410,000-510,000 lbf). Combined with more engines, Super Heavy Booster 7 could theoretically produce around 7600 tons (~16.7M lbf) of thrust at liftoff, while Booster 4 – which never fired even one of its 29 Raptor V1.5 engines – could have produced about 5400 tons (~11.9M lbf). That 40% increase in max thrust likely necessitated a similarly strengthened thrust section, involving a large number of mostly invisible design changes.

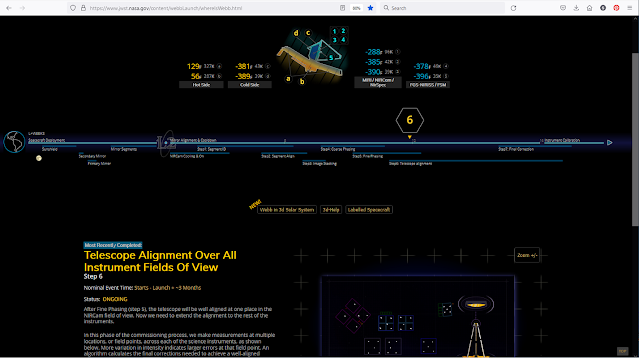

Those changes now need to be qualified and it appears that SpaceX may use B7 – an entire Super Heavy booster that could one day fly – to verify their performance instead of a cheaper, more disposable test tank. The first part of that testing will likely involve simulating the thrust of at least 13 of Booster 7’s engines. The test stand’s ‘cap’ could also be installed on top of Booster 7 once it arrives at the pad, possibly allowing SpaceX to simulate both the thrust of all 33 engines and the stress caused by acceleration during launch, reentry, and landing. Finally, SpaceX has begun installing a custom fixture and plumbing that will allow all of that structural testing to occur while Super Heavy is loaded with liquid nitrogen (LN2) or oxygen (LOx), adding another layer of stress.

Starship Super Heavy will have ~16.7 Million pounds of thrust?

More than twice that of the Apollo Saturn V's 7.5 million lb.s? I want to see that.

There are road closures scheduled for tomorrow with secondary days of Monday

and Tuesday. I don't know the status of Ship 24 which has been rumored to be paired with B7, even perhaps for the first orbital flight, but S24 will be using Raptor V2 engines as well and needs to begin testing, too. We don't know if they intend to move other things or start

testing B7, but these are becoming interesting times at Boca Chica again.